On 29 January, \I launched the joint OECD-APEC Report entitled “The Role of Education and Skills in Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Evidence from APEC Economies” during my mission to Chile. I launched the report with Teodoro Ribera, Chilean Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Rodrigo Yañez, Undersecretary of International Economic Affairs, Mrs. Isabel Loncomil, Co-founder of Lirmi Chile, and Mr. Pelayo Covarrubies, Director of “País Digital.” You can find the report here: bit.ly/2RVj2Zx .

Ministro Ribera, Ministra Plá, Subsecretario Yáñez, Distinguidos participantes, señoras y señores:

Es un placer estar aquí para presentar el informe APEC-OCDE El papel de la educación y las habilidades para cerrar la brecha digital de género. Este reporte es un resultado concreto de la colaboración entre la OCDE y Chile durante su año APEC, cuyos resultados han apoyado la Hoja de Ruta APEC sobre Mujeres y Crecimiento Incluyente que Chile impulsó en el contexto APEC. Seguiremos trabajando estrechamente con Chile y con las demás economías APEC en la implementación de esos importantes compromisos. Permítanme complementar lo que fue presentado en el video con algunas de las principales conclusiones del estudio APEC-OCDE.

Tanto en el caso de las mujeres como de los hombres, estar en condiciones de aprovechar todo el potencial de la transformación digital contribuiría a hacer más sostenibles e inclusivas las distintas economías y sociedades.

SIN EMBARGO, incluso a fecha de hoy, las mujeres van rezagadas en cuanto a las posibilidades que tienen de costearse herramientas digitales, y de acceder y hacer uso de ellas.

Acceso

- En todo el mundo se conectan a Internet unos 250 millones de mujeres menos que de hombres.

- Lo mismo sucede en las economías APEC. En todas ellas (salvo EE.UU.) se constató que fueron menos las mujeres que utilizaron Internet que hombres (la brecha de género más amplia fue la de Perú, con 5,3 puntos porcentuales de diferencia, seguida de las de Indonesia y Malasia, con 4,8 p.p.).

- Y no se trata solo del acceso a Internet, sino también del uso que hacemos de él.

- Más hombres utilizan Internet para buscar trabajo (las brechas de género más amplias fueron las de Chile con 9 p.p. y México con 5 p.p.).

- Las mujeres utilizan en menor medida servicios de banca por Internet en México (3 p.p. menos) y en Chile (10 p.p. menos).

- Las mujeres tienen menores probabilidades de utilizar servicios de Internet móvil. En México, por ejemplo, la probabilidad de que tengan teléfono móvil es un 5% inferior a la de los hombres y, de que usen Internet móvil, un 10% menor.

- Y las mujeres usan y desarrollan menos aplicaciones informáticas.

Asequibilidad

- Son numerosas las mujeres que no pueden costearse comprar y operar tecnologías digitales. De hecho, en economías de ingresos bajos y medianos el coste de 1 GB de datos puede superar el 5% del salario mensual. La asequibilidad puede representar una barrera importante para acceder a herramientas y medios digitales, en particular en zonas rurales y entre las personas socioeconómicamente desfavorecidas.

- ¡Se trata de un círculo vicioso!

- Los obstáculos a la asequibilidad perjudican particularmente a las mujeres. Se aprecia una correlación intensa y negativa entre los niveles de educación e ingresos de las mujeres y la brecha de género en la propiedad y el uso móvil de Internet (móvil).

Demasiado pocas mujeres cursan en las economías APEC los campos STEM.

- Las mujeres rondan tan solo un 27% de quienes obtienen un grado STEM.

- Incluso tras lograr matricularse en estas carreras, es mucho más probable que terminen por no graduarse, presentando además una probabilidad de cambio de carrera que duplica la de sus colegas varones.

- Entre quienes tienen un doctorado en TIC, hay casi 3,5 veces más hombres que mujeres, y, en el caso de un doctorado en “ingeniería, fabricación y construcción”, el porcentaje de hombres triplica al de mujeres; en cambio, las mujeres están sobrerrepresentadas en campos “menos técnicos”, como salud (79%), bienestar (75%) y educación.

- Esto responde a un bajo nivel de confianza entre las niñas. Nuestro estudio PISA (para estudiantes de 15 años) concluyó que, en todos los ámbitos, en preguntas relacionadas con sus competencias en ciencias y matemáticas, las niñas muestran un nivel de confianza un 10% menor que sus compañeros varones.

- Y en nuestra encuesta PISA las niñas manifestaron actitudes menos positivas hacia la competencia que los niños.

- De esto se concluye que las trayectorias profesionales comienzan a divergir antes de los 15 años, mucho antes de que efectivamente hayan de tomarse decisiones profesionales importantes.

- Estas diferencias en cuanto a niveles de autoconfianza y disposición a competir, así como la percepción de las mujeres de que las industrias tecnológicas estarían “masculinizadas” y, por tanto, dominadas por hombres, alejan asimismo a las mujeres de los trabajos e industrias mejor remunerados.

- Por ejemplo, en todo el mundo, el 90% del desarrollo de aplicaciones informáticas lo llevan a cabo equipos integrados únicamente por varones. ¡Como para extrañarse luego de que tengan un contenido violento!

¿Qué causas subyacen a la brecha digital de género? ¿Cuáles son algunas posibles soluciones?

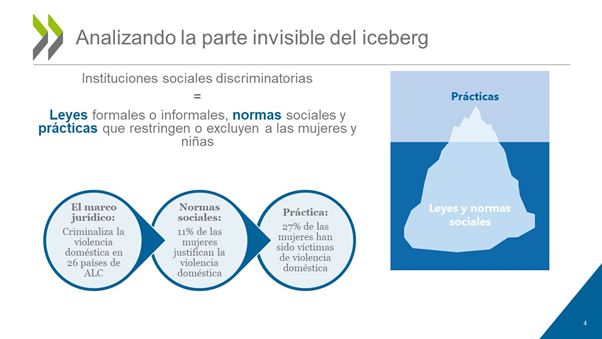

La falta de habilidades digitales, la falta de tiempo, la carencia de modelos (¡Porque no puedes ser lo que no puedes ver!), y sobre todo, los estereotipos y normas socio-culturales impiden que las mujeres aprovechen plenamente los beneficios de la digitalización. Cualquier solución debe hacer frente a estos desafíos desde la raíz y no perder de vista que:

Sin las políticas públicas idóneas, es probable que los obstáculos a los que las mujeres se han enfrentado —y siguen enfrentándose— en el mundo analógico se multipliquen en el futuro digital.

- Las intervenciones de política tempranas y sistémicas, orientadas tanto a los sistemas educativos como a cambiar las normas culturales y afrontar estereotipos, serán cruciales para abordar las brechas de género y evitar que estas se amplíen con el despliegue de la transformación digital.

Espero tener la oportunidad de comentar estas cuestiones con más detalle durante el diálogo con expertos en educación e ingeniería.