Keynote address as delivered on 25 April 2019 at the Economic Transition in the Anthropocene: Ensuring a Just and Sustainable Future for Humanity at the University of California Irvine.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I am delighted to join you for this conference on Economic Transition in the Anthropocene. I’d like to thank Leslie Harroun from Partners for a New Economy for the invitation and UC-Irvine for putting on this rich programme of speakers.

We gather here at the height of the Anthropocene. Human activity is having a decisive influence on climate and the environment.

We know from last year’s IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C that we have barely a decade to radically transform our economies and societies. We must slash emissions by 45% by 2030 if we are to have any chance of restricting temperature increases to 1.5°C.[i]

And yet, the World Meteorological Organisation has announced that the 20 warmest years since records began have been in the past 22 years, and the last four years have been the warmest on record.[ii]

For the first time in several years carbon emissions are rising again.[iii] Natural systems are moving beyond the boundaries that agriculture and ecosystems evolved within. This presents an existential dager to our civilisation and calls for radical action.

However, the level of ambition at the international level is wholly inadequate. To date, only 11 of the 197 UNFCCC parties have communicated their long-term, low-emission development strategies.

The prevailing economic models that pushed us to abuse the resources and upset the balance of our natural environment, also led us towards unsustainable and unjust approaches to the economy and society.

We gather here more than a decade since the subprime crisis triggered a cascade of events that ripped through the global economy and almost caused the total collapse of the world financial system.

Few saw this coming. Nor did they foresee how the financial crisis would lead to the Great Recession, nor how this Recession would produce a crippling social crisis and derail our politics, in turn threatening the recovery further.

This is a tough lesson in political economy, the likes of which we have not seen in Europe since the 1930s.

The economic crisis has turned into a social crisis. As Dennis Snower says, social prosperity has become decoupled from economic prosperity. This, in fact, predates the crisis, so there can be no question of just fixing a few bugs or imbalances in the global financial system and going back to business as usual.

Sustainable, inclusive growth will only be achieved if we coordinate economic, environmental and social policies to make them work towards a common goal, and not, as can often be the case, in conflict with each other.

We cannot do that if we continue to use the traditional methods, based on silos, treating problems as if they were distinct from each other, and seeing economic growth as a goal in itself.

In fact, our common goal is, or should be, well-being, but when we look at the different areas that well-being covers, the signs are worrying.

They are telling us that we need radical change. Policy-as-usual will not do. We didn’t do enough to address inequalities and global interconnections, and the world is manifesting this failure.

Let’s take a look at some of the headline numbers.

The income gap in the OECD between the top and bottom deciles has grown over the past three decades in most OECD countries. The average disposable income of the richest 10% of the population is now around nine and a half times that of the poorest 10% across the OECD, up from seven times in the 1980s.

Social mobility is stalling. The OECD has estimated that it would take four to five generations (around 150 years) for children from the bottom earnings decile to reach the level of mean earnings !

Economic inequalities are translating into social divides, with compounded effects. The OECD report Equity in Education: Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility, released last October, shows that by the age of 15 disadvantaged pupils have fallen on average two-and-a-half years behind their more affluent peers. This ends up being almost impossible to make up in the short years of education that are still ahead of them. The damage is done.

There is also evidence that some negative economic trends are now affecting new layers of the population, as shown by the report we released last week: Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class.

The study found that over the past 30 years across OECD countries the median income has grown a third less than the average income of households in the top 10%.

Half of middle-income households struggle to make ends meet and four in ten are financially vulnerable, meaning they are in arrears or unable to cope with unexpected expenses or sudden falls in income.

The cost of housing, education and healthcare has risen well above inflation and with every generation the middle class lifestyle is becoming less and less accessible to young people.

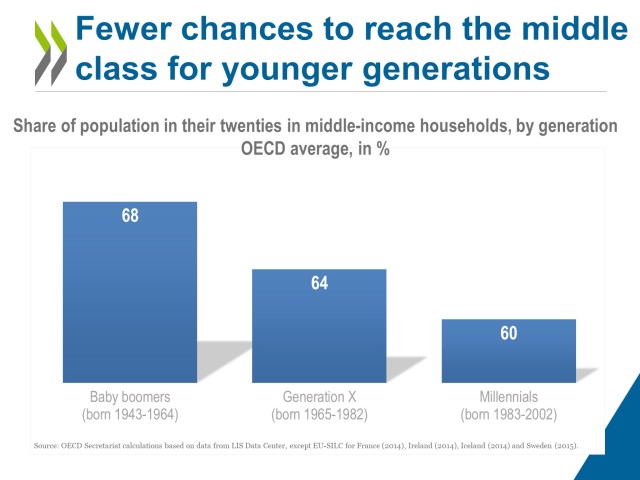

The middle-income group has grown smaller with each successive generation: 70% of the baby boomers were part of the middle class in their twenties, compared to 64% of generation X and 60% of the millennials today.

People have been left behind, and unsurprisingly we are seeing anger at unfair outcomes translating into a decline in trust.

In the OECD’s work on going beyond GDP to measure progress, we show that trust between individuals (interpersonal trust) and trust in institutions (institutional trust) are a decisive determinant of economic growth, social cohesion and well-being.

Countries with higher levels of trust tend to have higher income. High-trusting societies are more equal, while low-trusting societies show typically higher levels of income inequality.

Institutional trust is a key element of a resilient society and is critical for implementing effective policies, since public programmes, regulations and reforms depend on the co-operation and compliance of citizens. Trust is therefore a crucial component for policy reform and for the legitimacy and sustainability of any political system.

Yet in OECD, only 43% of citizens trust their government.[iv] In the absence of trust our societies have fragmented.

This in turn is producing worrisome democratic outcomes, including gains in nationalist, extremist and populist parties.

Populism, which brings no solutions, only blame and conflict, is making governance even more difficult and it is contributing to mounting protectionism, which in the long-run will do even greater harm.

Protectionist measures are harmful to the economy and costly precisely to those that it claims to protect. Recent OECD data has estimated that each dollar of new tariffs costs global households 40 cents, while each dollar of tariff reduction adds 90 cents to global household incomes. [v]

We can close our borders and try to shut our eyes to the reality of an interconnected world, but in the end, we will all be worse off if we deny ourselves the benefits of co-operation and common solutions to shared challenges.

Many of the challenges we face are inherently international, from migration flows, to epidemics and the implications of technological change.

Digital technologies are having a profound global impact, transforming all sectors of the economy, not only those that are ICT intensive. The digital economy is fast becoming the whole economy. This transformation is changing practically every aspect of life, from the way individuals work and study, to how they communicate, buy goods and services, or spend their free time.

Digital transformation alters the way businesses, governments and other organisations interact and operate. And it is changing the global landscape of science, technology and innovation, with emerging economies playing a growing role, especially China.

Many people compare these changes with earlier industrial revolutions, steam or electronic technologies for example. However, this transformation is truly gobal and is taking place at an unprecedented pace. More than 50% of the world’s population is now connected to the Internet, with the share in developing countries increasing from under 8% in 2005 to over 45% at the end of 2018.[vi] In the OECD, the number of mobile broadband subscriptions has increased by more than 50% since 2012, so that there are now more subscriptions than people.[vii]

Digital transformation is bringing many opportunities for sustainable and inclusive growth. Despite fears of technological unemployment, we also know that four out of ten jobs were created in highly digital-intensive sectors over the past decade. Yet these are not necessarily being created in regions and among populations where jobs are being displaced or lost.

Many workers are worried about automation. The OECD estimates that automation could threaten up to 14% of jobs on average, with the low skilled and low-paid most at risk. We expect another 32% of jobs to see significant changes in how they are carried out.

If skills demand shift at the speed these estimates suggest, workers would have to continuously adapt their skill set over a working lifetime. This has major implications for education and training systems and underscores the importance of building the adaptive capacity of students and developing robust systems for lifelong learning.

This is not just about promoting digital skills but also a broader and softer skills set. Evidence points to the fact that the future is about pairing digital technologies with cognitive, social and emotional skills, and values of human beings. Educational success will no longer be about reproducing content knowledge, but about integrating what we know and applying that knowledge creatively.

Digital disruption is also bringing profound implications for competition dynamics. Today, new technology and the big players in the platform economy are highly concentrated. Only 250 firms globally generate 70% of R&D and patents, and 44% of trademarks.

Firms in the most digital-intensive sectors enjoy a 55% higher mark-up than firms operating in less digital-intensive sectors, and global acquisitions of digital-intensive firms grew by more than 40% over 2007-15, compared to 20% for acquisitions in less digitally-intensive sectors.

For this reason, we need to address weak competition frameworks in the digital and knowledge-based economies, which can unleash “winner takes all” dynamics.

As Joe Stiglitz points out in a new book to be published this week, People, Power, and Profits: Progressive capitalism for an age of discontent, growing concentration of market power allows dominant firms to exploit their customers and squeeze their employees, whose own bargaining power and legal protections are being weakened.

The OECD is taking action to help countries steer technological change for good. In particular, we have been working on a global multistakeholder response to the challenge of how to achieve transparent and accountable artificial intelligence systems.

We have developed a Recommendation to underpin responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI, which will facilitate innovation, adoption of, and trust in AI, to maximise potential, while minimising risk.

This Recommendation has at its core a focus on inclusive sustainable growth; human-centred values and fairness; transparency and explainability; robustness, security and safety; and accountability. It also identifies critical actions for governments, and importantly, calls for international co-operation, so that we can progress together on AI policy and related technical, ethical and legal issues.

The question is not just about how to ensure participation and skills for the digital revolution, but also how to ensure that we shape the evolution of technology so that it contributes to our well-being goals and opens up opportunities for those who risk being left behind.

In short, how to put in place structures and strategies to ensure everybody wins and can participate, not only as technology takers, but as technology shapers, including women, who make up less than a quarter of ICT graduates.

So this is the context of spiralling inequalities and emerging challenges in which “we need new approaches to economic thinking and acting”.

Simplistic neoliberal economic models, which do not capture reality or reflect the importance of inclusiveness and multidimensional well-being, are incapable of addressing these problems. Just as they failed to anticipate or prevent the financial crisis.

This is why the OECD has fundamentally changed the way that it understands, analyses and promotes economic growth. Growth is not an end in itself, it is a means to an end. It is a means to achieve better lives. We have put people, their well-being, their needs and aspirations at the centre of our approach.

The OECD has worked hard to address the shortcomings of traditional economic models and to develop a systemic perspective on interconnected challenges.

This is why in 2012 we established the New Approaches to Economic Challenges initiative (NAEC), to better understand the nature of the global economy, and its level of complexity and interconnectedness. Working with strategic partners like P4NE, we are identifying the analytical and policy tools needed to deliver inclusive and sustainable growth. With this knowledge we are bringing new models and we are also crafting the narratives best able to convey solutions to policymakers.

However, despite this effort, we continue to see in many countries, sectors and institutions a lack of understanding about the level of interconnectedness and interdependence in our economies, as well as an overemphasis on quantitative economics to inform policy.

Traditional models that are still widely used to study today’s economy make too many assumptions that are at odds with the facts, while at the same time wrapping themselves in claims to objectivity and scientific rigour, which make them very difficult to contest.

The very name of these models, general equilibrium, shows that they assume that the economy is in balance until an outside shock upsets it. These models are based on assumptions that people are rational, take the best decisions according to the information they have to maximize utility, and that the accumulation of rational decisions will deliver the best outcome.

We know that this does not reflect reality. Look at the referendum on Brexit. People’s lives and choices are shaped by their hopes, aspirations, history, culture, tradition, family, friends, language, identity, community and other influences, some of them are relatively new, like social media.

Macroeconomic models neglect these elements. The social and human sciences like psychology, history and sociology, for example, that can explain these variables with depth and nuance have been left out of the equation, quite literally.

This traditional view is essentially linear, and the policy advice it generates is tailored to a linear system where an action produces a fairly predictable reaction. It looks at aggregate outcomes and at average results. It does not capture the richness, the contingence, the interdependence and the complexity of human actors and the economies they operate in. This is what we are trying to revisit with NAEC.

Economic models that rely only on inputs such as GDP, income per capita, trade flows, resource allocation, productivity and representative agents tell part of the story, but they do not paint the whole picture.

Crucially, they fail to capture the distributional consequences of the policies we make, and do not address the fact that the growth process has left too many people behind. They do not capture natural resource depletion, or incorporate environmental damage as liabilities. On the contrary, they assume that, by growing the pie, inequality of income and opportunities will trickle-down, or that you can always clean up the environment after you grow. In fact, much of the damage we are seeing to biodiversity, like coral bleaching and species extinction, is irreversible.

Traditional models do not integrate important dimensions such as fairness, trust or social cohesion that are not easily measurable. As our Chief Statistician says, we need to measure what we treasure, not just treasure what we measure.

Above all, we need a new approach to economics that goes beyond the quantitative dimension. This requires a full re-vamp of our analytical frameworks and assumptions and it also requires a broader shift towards a more empowering state.

We need a high level of ambition to respond to the current situation, on a scale of those enlightened leaders who created the welfare state in the first half of the last century. With the rapidly-changing landscape and policy challenges we are facing in the twenty-first century, there is a need to change the scope of the State. We need to overcome the frameworks of liberal economic theories that dictate that the state only intervenes in the event of a market failure. We can do better than that. We do not propose an overwhelming State, but we need to shape a new role for the state, an empowering State, one that ensures that it levels the playing field for people and addresses concentrations of income, opportunities and wealth.

Our mission must be to redefine the purpose of the economy, to ensure governments, corporations and banks serve society’s interests, and not the other way around. We have to broaden the objectives of policies to include not only material well-being but dimensions such as health, quality jobs, a sense of belonging, social cohesion, and environmental outcomes.

Integrating these proposals into a coherent synthesis ultimately means proposing a new framework that redefines the nature of well-being to balance economic, social and environmental capabilities. This requires leadership, theoretical debate, institutional change, new tools and methodologies.

We know that the world we live in is a system of systems, physical or not, that is complex.

That means you have to take a systemic approach that can deal with tipping points, phase changes, emergent properties, and – very important for us – the fact that shocks do not always come from outside. The system itself produces the shocks that destabilise it.

New approaches, tools and metrics will be adopted and mainstreamed more easily if they are embedded within a broader narrative of inclusion and empowerment.

Hannah Arendt put it very well in her book Men in Dark Times when she wrote that: “No philosophy can compare in intensity and richness of meaning with a properly narrated story”. Stories are one of the most pervasive features of human culture. They are how we make sense of the world, how we see our own role within it, and how we pass our cultures onto the next generation. Narrative is the bridge between what we feel as individuals and how we formulate and explain that experience.

Stories may be as old as time itself, but they are as important today as ever. Narrative has direct relevance for the policy options we favour and the people we choose to formulate and implement them. We are seeing time and time again in the current political context that facts do not speak for themselves. They need someone to give them a voice by crafting the narrative.

Unfortunately, some populists do this very well. The narrative of the populists is very straightforward. They play on people’s fears and emotions, offering a simple explanation for and simplistic solution to complex problems.

For populists there is always someone out there to blame. They exploit people’s sense of injustice, loss of trust and feelings of betrayal. They use action-oriented but nebulous slogans like take back control or close the borders to undue influences.

It may be hard for us to admit it, but these are empowering narratives, promoting the idea that the person who hears them can do something. It makes them feel part of the story. It connects with their emotions and values.

So we need an empowering narrative too. One that connects with people and brings them together around common values of inclusiveness, fairness and solidarity.

So, what might a new, empowering narrative look like? One that moves people and leaders towards more inclusive and sustainable growth models and that builds a caring world. We need a narrative that champions values which may be difficult to measure but which are integral for well-being, opportunities and outcomes – fairness, trust, cohesion, a sense of solidarity, community and belonging.

This empowering narrative should be based on the best facts and science available and should contribute to the global effort to produce a new social contract that brings back hope and trust.

At the OECD we are making the call to turn this analysis into action, but this will require a re-engineering of the institutional settings in OECD economies, getting rid of silos and having a holistic approach for the well-being of people, that is multidimensional.

We are bringing an array of new tools to help policymakers do this. Just last year the OECD produced the Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth, including detailed recommendations and a dashboard of 24 inclusive growth indicators to monitor progress over time.

It’s not just about GINI co-efficient, which is important, but does not tell you everything. Let’s look at the bottom 20% to the bottom 80% and see how that figure evolves.

We need to look at gender gaps, not just in income and other outcomes, but also in emerging areas like digital skills. We need to tackle gender stereotypes and understand better how they are perpetuated by the media, especially social media.

We need to look at how easy it is for children aged 0 to 5 years to access high quality education and let’s look at how socio-economic background affects school performance and let’s measure socio-emotional skills and well-being amongst students, not just cognitive skills.

This is one of the important directions in which our Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is moving, in particular with the Global Competence Framework, because we understand that it’s not just about what you know, it’s about your adaptability, your flexibility, your critical thinking, your ability to tell fact from fiction, detect fake news and to cope with pressures from social media, for example, particularly in the case of girls.

There are concrete actions which can make a huge difference. Like significant investment in early childhood education and care, or to mention another area in education, like putting the best, most experienced teachers in the toughest schools or using gender neutral textbooks.

To promote fairness and ensure the services have the resources to function effectively and ambitiously, we have to take measures to ensure top earners pay their fair share of tax. This is an area where the OECD has been a world leaders, with our Common Reporting Standard for Automatic Exchange of Tax Information; almost 100 jurisdictions have now commenced exchanging automatically, returning 93 billion euros to public coffers.

The OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project has also been a game-changer for tackling tax avoidance and evasion, when you consider that annual global revenue losses from base erosion and profit shifting amount to between 100 billion and 240 billion US dollars. And that’s the conservative estimate!

So everyone has to pay their fair share, but if we are to succeed in shaping the empowering state, we also need business on side, not just as tax payer, but as an advocate and agent for inclusive growth.

This is why we recently developed our Business for Inclusive Growth Platform (B4IG) to unite businesses and governments behind a common agenda.

These policies are helping make advance the agenda, but we need more than incremental change, more than tinkering at the edges of the status quo. Meaningful progress will require a re-engineering of the institutional settings in OECD economies, getting rid of silos and having a holistic approach for the well-being of people, that is multidimensional.

The OECD is bringing an array of new tools to help policymakers do this. Just last week, NAEC convened some of the world’s finest experts to show the OECD policy community how network analysis, agent-based models, machine learning and other state-of-the art techniques could help to improve their policy advice.

It is deeply encouraging to see that so many people across the world are interested in what we are doing, with 800,000 viewers following the seminar, which we livecast online.

This demonstrated, including to our own Members and Directors, that the work of NAEC goes to the heart of what our citizens need and the radical change so many of them are asking for.

NAEC can federate and focus this positive energy for change. It has already changed the face of the OECD, but this is just the beginning. With your ideas, your help and support we can grow and empower NAEC to reach more people and centres of decision-making power and influence.

I very much look forward to hearing over the course of this conference how we can work together to design, develop and deliver new approaches to economic thinking and acting.

Thank you.

[i] “In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range).” From https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2018/07/SR15_SPM_version_stand_alone_LR.pdf

[ii] https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/wmo-confirms-past-4-years-were-warmest-record

[iii] https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-46347453

[iv] http://www.oecd.org/gov/trust-in-government.htm

[v] In-house calculations, TAD, 2018

[vi] ITU (2018), “New ITU statistics show more than half the world is now using the Internet”, December 6, https://news.itu.int/itu-statistics-leaving-no-one-offline/

[vii] Going Digital: Shaping Policies, Improving Lives (OECD, 2019) p.38